The naked and the wet

The naked and the wet

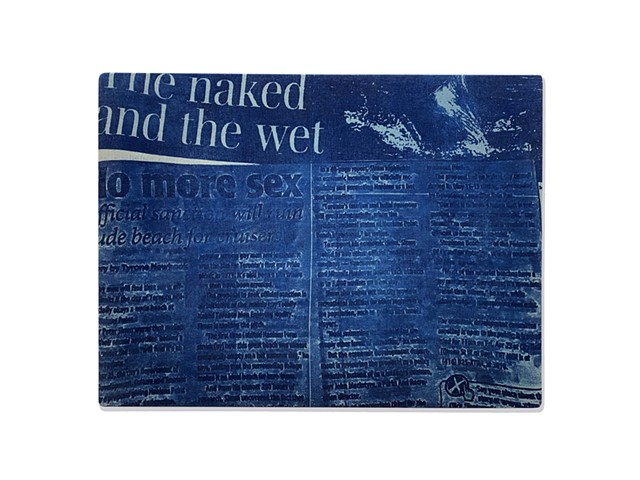

The week that my residency started at Artscape Gibraltar Point was the same week that Hanlan’s Point Beach was officially acknowledged as a queer historical site. In preparation for this residency and to respond to the site, land, and nearly a century of queer history that I was about to engage with, I immersed myself in The Arquives: Canada's LGBTQ2+ Archives collections. I pulled newspaper clippings, ephemera that traced the history of the first Pride Picnics and Gay Days on Toronto Island, and legal documents detailing the legislation around Hanlans Point clothing-optional beach.

The City of Toronto’s acknowledgement of Hanlans Point as an official queer historical site came as a relief as the Ontario government continues to target and endanger this site, indigenous land, and its history with recent proposals for privatized concert venues and spas. The words of articles from decades past read all too familiar—“Of all places for Toronto City Council to approve the location of the city’s first nude beach, Hanlans Point is the least appropriate. The site makes a complete mockery of what Ned Hanlan, Canada’s first national sports hero, represented to a young nation striving to establish its own identity” (Dave Di Felice, Toronto Star, 1999). Over and over again Toronto Islanders, Naturist Communities, Artists, Activists and Queer Stewards of Hanlan’s Point have protected this site from disappearing and continue to do so. Friends of Hanlans, an advocacy group dedicated to maintaining and safeguarding the site's history, have significantly contributed to this official acknowledgment.

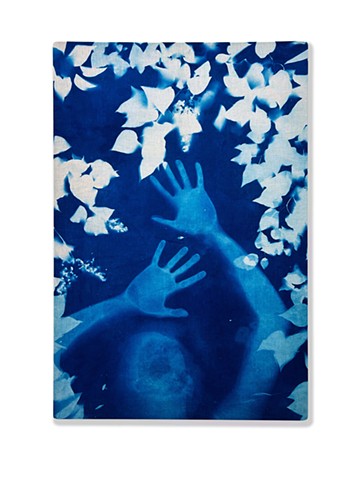

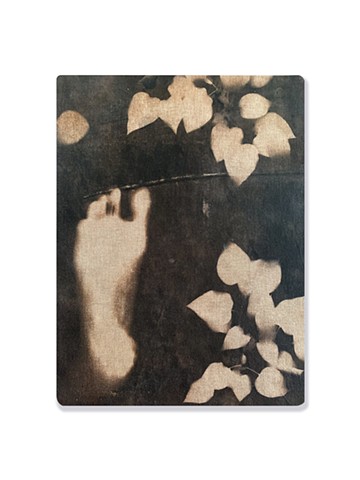

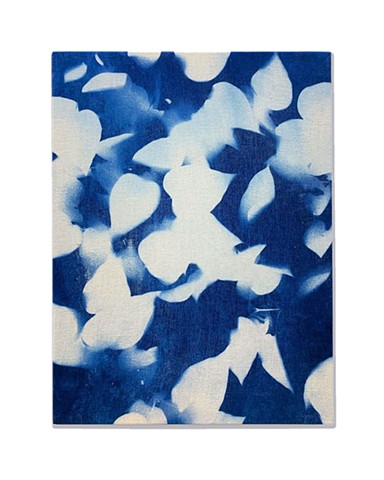

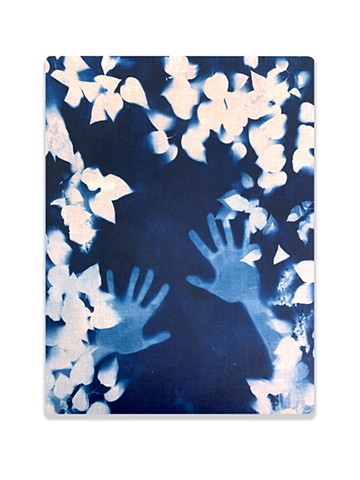

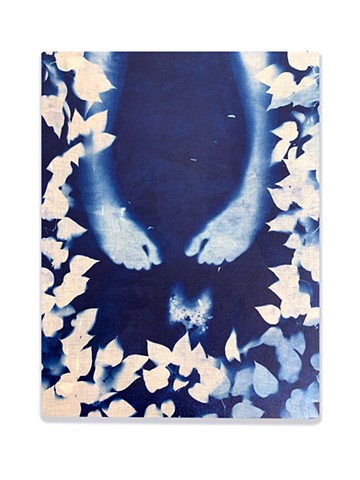

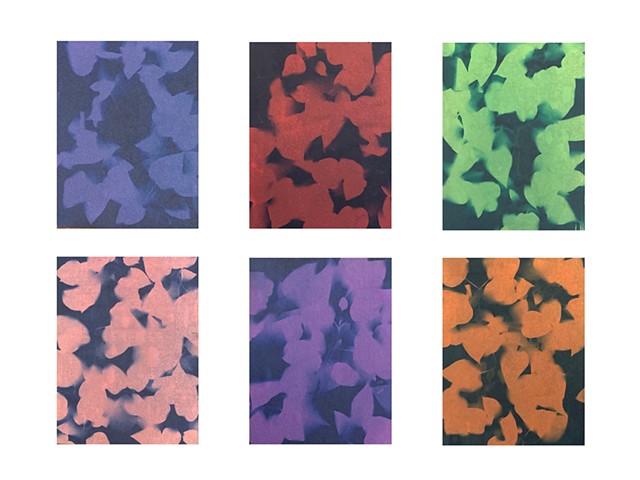

During my residency, I made a series of prints on the beach, using the sun, the water, and the landscape. Laying on the sand on top of cyanotype-coated fabric and paper, I performed as the leisurely beachgoer, the bush cruising body, and the closeted nudist, utilizing and enjoying the beach that we have been afforded, as a queer safe space. I documented my body, the queer body almost ethnographically, as evidence. Referring to cyanotype's original conception as a botanist’s tool for documenting species, I documented the queer body in this officially queer site, as a historical moment. Partially textile, photography, printmaking, and painterly, the medium is not made obvious, what is obvious is that a trace has been left, by the spectral body, and by history.

I used the foliage found on the shoreline to contextualize the prints alongside my body, in this series I use lilac branches and their heart-shaped leaves to refer to a history of the colour lavender, sapphic love, and queer symbolism.

"That mystic garland which the spring did twine

Of scented lilac and new-blown rose

Faster than chains will hold my soul to thine

Thro’ joy, and grief, thro’ life -- unto its close."

Kate Chopin’s ‘To the Friend of My Youth: To Kitty’, 1900.

The use of the lilac has multiple references however, as an invasive species lilac arrived in Canada only through colonialism, now naturalized, the purple flower is found all over southern Ontario. Its use reminds us of the land that we’re on, though now recognized as a queer historical site, this land has been cared for and utilized long before it was a queer site.

From pivotal queer histories of political and community action, ecological preservation of freshwater dunes and biodiversity, and indigenous land protection and sovereignty—we are indebted to this land and must protect it and its histories.

This work was made with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts during a residency at Artscape Gibraltar Point, Toronto. I want to also acknowledge my appreciation for The Arquives collections and printing by Smokestack Studios. Without them, this work would not be possible.

This work has been exhibited in Untapped, Artist Project Toronto, Better Living Centre, 2024, and auctioned at Art Attack!, Buddies in Bad Times Theatre 2023 and

Peripheral Review 2023